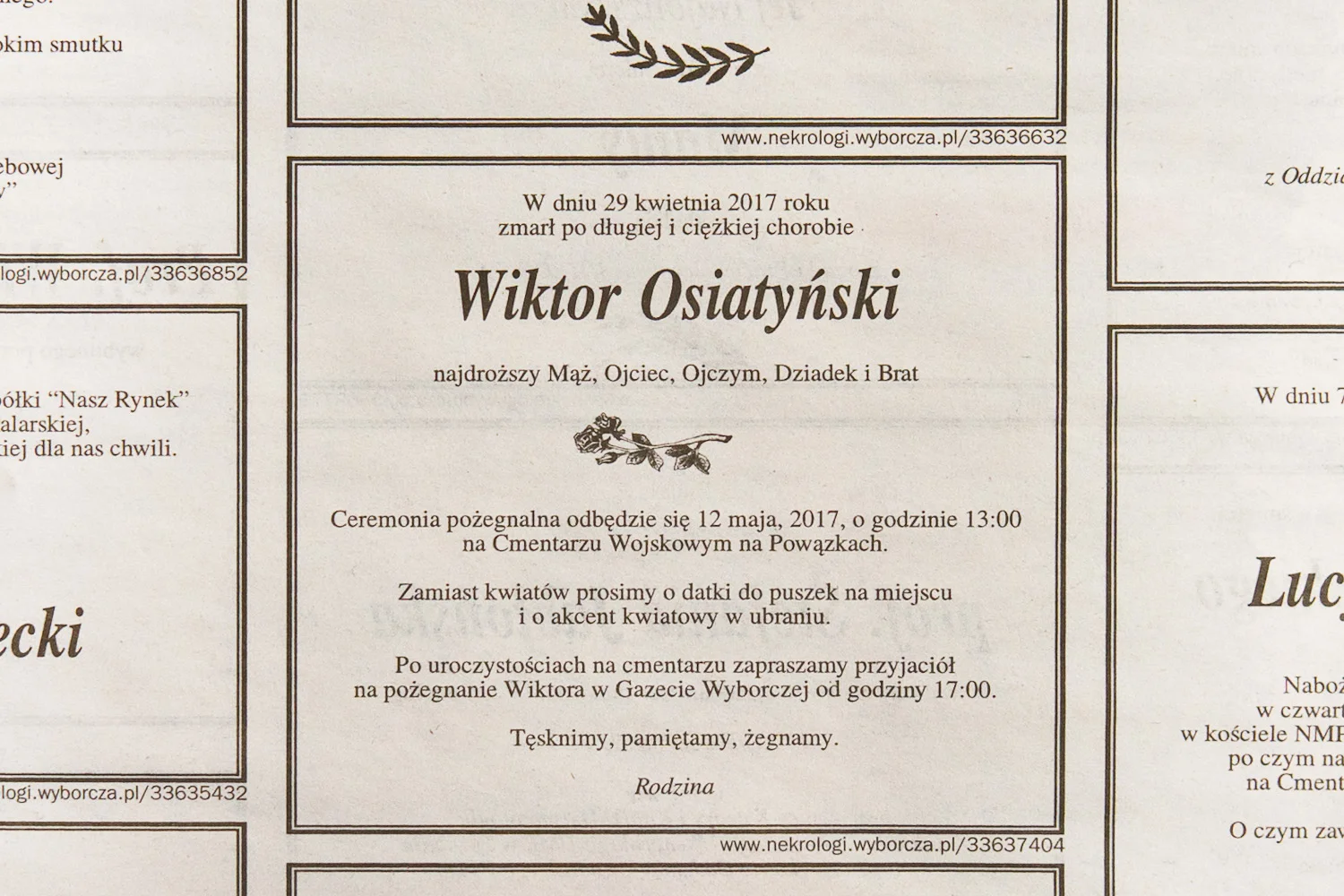

Our family’s memorial notice in the newspaper, amid another day’s torrent of the condolences from friends and institutions that helped us through the hardest of times.

One week ago my dad got the funeral he deserved: big, non-traditional, overflowing with gratitude expressed and remembered. The day was a Friday, sunny and quiet—a harbinger of the summer to come. Guest speakers delivered their eulogies and their fondness sometimes seemed at odds with their sorrow. When I spoke, I spoke about what I imagined my father would have been grateful for himself, could he be there (that so many people had come to celebrate his memory; that he had been allowed to die at home, with me and my mother by his side; that the liberals had finally scored one for our side in France). I recounted the time he told me, maybe a decade ago, that he believed the meaning of life was to create a surplus of kindness in the world. (Make no mistake, I said, he did not always have the patience to be kind, but he did regard kindness as the highest of virtues.) That day had been a quiet and warm one as well.

When my father was nearing death, I would occasionally turn to the poems he loved most, ones directly and indirectly about dying. I imagined I would find solace in them after his passing, and make them central to my experience of grieving, with its sleepless nights and requirement for verbal decorum. Startlingly, the very Iwaszkiewicz eulogy I translated into English for my father’s seventieth birthday, two tangled years ago, never made it into the speech I gave at the memorial. Just as in life my dad seemed perversely unafraid of death, his death has been impervious to poetics on dying.

Grief, I am discovering, consists not of epitaphs and tears, but of bewilderment and a sense of waiting (as if for the heaviness to lift, or merely for the pain to become unremarkable). My loss is not merely of the wonder that was a father’s love for an only daughter, but of the chance to right wrongs long abandoned, by both of us, and ones just uncovered.

My father’s hand, adorned with a tiny heart-shaped scab that did not escape my attention. Photo taken in Siena on May 19, 2006—an astonishing 11 years, 11 months, and 11 days before the day my father would die.