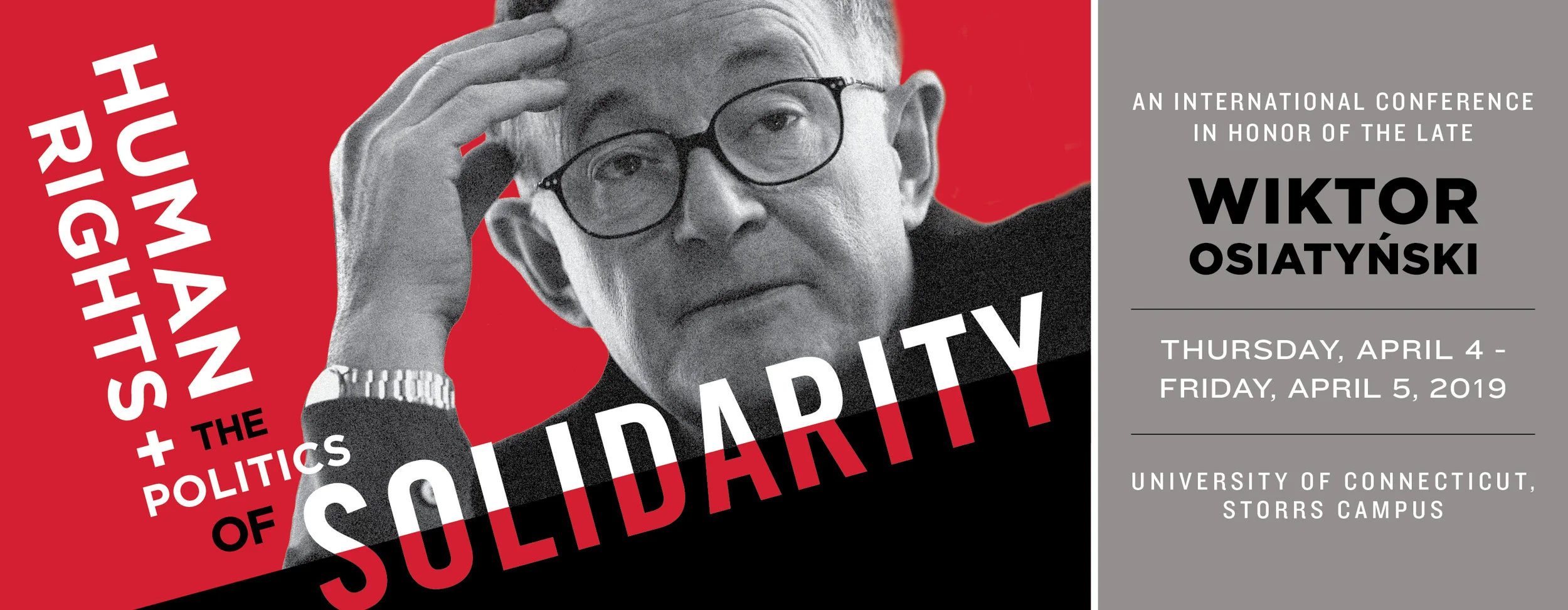

It is ironic that the transatlantic journey my son and I took in memory of my father is the very one he should have lived to see.

I am left with a heart full of wonder and thoughts zapping in response to the conference we attended— about people’s vivid memories of my dad and about the importance of the work being done by scholars like Kimberly Theidon, activists like Mai Khoi and Gerardo Reyes Chávez, and so many others. Were I to list the people whom I would like to thank, this post would be dense with names, and incomplete at that, because some I never caught, though memories of such meetings linger. Enough—this was never going to be an event summary. Instead, I’ll post the written version of my opening remarks, a spoken-form essay I put together over the course of the month or so preceding the conference.

PREAMBLE

I’ve heard that it is helpful when speaking before an audience to bring an object to ground you. I chose something some of you might recognize. Who remembers my father’s ties? I would give him all these suave ones, solid colors, understated, and he never wore them. But Van Gogh? Wild florals? You bet. We did a floral motif at the funeral, too. The crowd was huge, hundreds of people had come, many who knew him but also many who didn’t, who wanted to support what he stood for. Not everyone had the audacity to break protocol and wear something colorful, but enough of us did that it seemed like a sea of flowers. It was beautiful. And just a little outrageous, which was perfect.

I. A DAUGHTER’S PERSPECTIVE

When Kathy reached out to invite me to attend the conference, she suggested I say a few words about my father’s work in Poland, and about his legacy. As you’ll discover, I’m not really equipped for this task. What I can talk about is the dad I had. What his work meant to him. The price we paid for it, with him so determined, so jet-lagged, so preoccupied. (Don’t worry—I have few complaints.)

As to the ways my father’s work is outliving him in Poland, I can report that the left-wing newsgroup OKO.press has launched a watchdog initiative called Archiwum Osiatyńskiego, which pops up on lefty Facebook newsfeeds daily and seems to have really taken off. As you know, there is no shortage of news for a rights watch group to be outraged about in present day Poland (or here, or anywhere). Though it doesn’t end at outrage, of course, there is much to be done and the people at OKO.press are doing it. There are also at least two books in the making, one compiling my father’s celebrated radio interviews from the last decade of his life, which my mom is involved with, and another, with the working title Alfabet Wiktora Osiatyńskiego, which will be a glossary-style anthology of my dad’s achievements and teachings. There may well be more going on, but please understand that I live a bit of an expat’s life back home. My main news source is The New Yorker and I’m usually a few months behind.

Now, let me take you behind the scenes of a life I remember, and also behind the scenes of my loss. Because it turns out that grieving can be a source of much that is good. This, too, is a gift I count among those I got from my father.

II. COMMON GROUND

My dad was a complicated man, especially with members of his family. He was always prepared to take on the big things: the meaning of life, building democracies, social reform. But when it came to sharing a bathroom, or picking a restaurant, there was tension. I think my dad was the sort of social, often gregarious introvert that winds up burning through a lot of energy to sustain the extroversion required for his work, so that when he’d come home and shut the door there’d be nothing left. In many ways, my parents’ marriage thrived on the time they spent apart, and so did my relationship with him. (Yes, I did get my mom’s permission to say that.)

He and I were both territorial and stubborn, and just amazingly incompatible. He liked clutter, I liked minimalism. He liked his Mahler loud, I liked the music off. Because he was often absorbed in his work—sometimes across an ocean, often across the table—our relationship adapted to engaging from afar. I was a college student in this country, and then a grad student. During those years, I developed a special closeness with my dad, mainly because we would often be in adjacent time zones. And that, some of you know firsthand, makes an amazing difference, even now, when calling is free the world over, and it made even more of one in that era before Skype. Over the years I developed a real facility for containing a lot of my relationship with my father in my mind, and this persisted even after we were living in one city, and in one building, even. So instead of arguing over table manners we connected over the big issues, or we connected wordlessly, and I felt in touch with my father even though we didn’t need to do a whole lot together.

One thing we found mutually rewarding were opportunities to collaborate on those aspects of his work that overlapped with my interests and expertise—branding, creating things like book titles, editing English text, the semiotics of posters and book covers. This was the visual, typographic realm of marketing communication, or it was the sphere of a language foreign to him but practically native for me. Not only did he appreciate my help and welcome it, he really needed a pair of eyes to help him see in these particular dimensions. There were even a few occasions when the dynamic flipped, so when I had a poem I’d be translating, from or into Polish, my dad would weigh in, with tremendous insight, illuminating aspects of Polish culture and literature that my international schools and American universities hadn’t covered. Again, for both of us, this would be the kind of thing Maslow called a peak experience.

As I was preparing for this conference I reviewed some of these collaborations, like the title options for the book, Human Rights and Their Limits. I had prepared this over-the-top four-way comparative analysis of his original title, Human Rights and Other Values, which the publisher didn’t want, along with the title that was ultimately chosen, plus two more: The Limits of Human Rightsand Human Rights and Democracy. This was 2009. I mentioned being incompatible, but here we were complementary, useful to each other, able to hear each other and work together.

We ran with ideas. We really thrived on explaining stuff to each other.

III. LATE MIDDLE GRIEF

Interestingly, this current in our relationship has proven well-suited to separation by death and the ensuing grief, because it is possible and nearly effortless to take a leap from the kind of relationship I described to one that’s entirely a product of intuition and imagination.

There were two things I remember most vividly from all the words of support I was offered in the days following my dad’s death. One was a quotation from The Art Loverby contemporary American writer Carole Maso, “So little goes with the body of a man. So much is left behind.” The other was something several people said, and it was another great source of comfort and hope, namely that when a person’s life ends, the relationship does not, but that it in fact continues. This has proven to be true in my case, and it helps explain why coming here really had an urgency for me that I keep comparing to an opportunity to see my father again.

The loss is still new but no longer raw. That suffocating sadness is gone, in fact, I think it’s what finally taught me to breathe. Today, 705 days later, there are no corners for the pain to come flying out of. There is no void, because it has filled itself with breath. And with new layers of a father-daughter relationship. And also with the kind of sadness that seems to be a precursor of happiness (and maybe you have to be Slavic to understand that this is an actual thing).

For me, born to privilege and to parents so charismatic and successful, it is only now that I can rise to really celebrate my dad’s greatness with exuberance. When he was alive, it was not so easy. I am always attentive to other people whose parents have accomplished great things when they report feeling like a child despite being well into adulthood in terms of years. Because it is not only pride and awe that one feels when her parents’ careers keep gaining momentum even as most parents of that generation are going into retirement.

And please consider this: if he had lived, it would be him here now commanding all this attention from this esteemed crowd. And my son Anker and I, well, we would be in Warsaw, emailing grandpa, wishing him a good couple of days in Connecticut.

So in this stage I’ll call “late middle grief” (to riff on something Siri Hustvedt wrote about childhood) I am also discovering that it is possible to exult in pride and gratitude for a father’s accomplishments. And it occurs to me that what took him away, literally and in units of attention—this is now what is giving him back. To me, to our whole family. His legacy—this, you—that is what’s keeping him alive.

There are many of you with serious careers in this room, and you will miss some of those ballet recitals and baseball games and maybe even some birthdays and graduations, and I am basically saying that sometimes that’s OK.

IV. ARCHETYPE: TEACHER

“I’m not worried about you at all. I don’t doubt for a second that you will find your way.”

That is a very interesting and unique way of telling someone “I’m proud of you,” because, unlike “I’m proud of you,” it is condescension-free, it is not another way to be right. Instead, the emphasis is on trust and acceptance and wonder. I heard this often from my father in the last phase of our life together, after I had become a mother and after my work began to take shape. I think back to the affirmation that this was at the time and that it continues to be—“I have my full confidence in you, I know you’ll be OK”—and I am grateful, heartened and encouraged.

Grateful, heartened, encouraged. It may well be the ability to instill this in others that makes a great teacher. My father searched for meaning as a writer, as a critic, as an activist, and he was gifted at many things, but I think at heart he was ultimately the archetypal teacher, which is why his work right here, at this university, was some of the most satisfying he got to experience.

It follows that the recognition he got for his teaching is what brought him the fullest satisfaction. The look on my dad’s face when those student evaluations came in, or his affect as he was grading papers, and of course being honored by the universities at which he taught, this is where he found purpose and triumph and joy.

Because maybe that other thing that makes a great teacher is her or his delight in teaching itself. Seeing it as a privilege. Boundless energy for it. Curiosity and respect in abundance. A gift for speaking eclipsed by an even bigger one for listening. Wearing authority with ease. Helping others find truth, a calling, and new levels

of perseverance and courage. It was his students who might have experienced this side of my father in its purest form, but so did his colleagues, and so did I, because parenthood consists of many things, but teaching is a fundamental part of it, maybe the most essential.

V. A POEM FOR MY FATHER

Some of you will remember my father reciting poetry during his speeches and in conversation. Of course he probably did this more when conversing and lecturing in his native language, so you may have to take my word for it. In memory of this wonderful practice of his, I felt that a poem is called for today. I even enlisted friends online to find the right one—something by a Polish poet, something my father might have known, something that evokes the political and social themes at the heart of this conference. Optimistic, not too bleak. I was about to choose something by Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska or by my dad’s favorite poet, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, when I was struck by an unexpected idea.

The poem I want to read today is not by a Pole, and it is not about democracy. It’s one I discovered when my son was an infant, and it made a deep impression at the time, yet I never got around to sharing it with my dad. Today gives me an opportunity to remedy that. Did he know it? I’m not sure. Not long ago, around the time of what would have been my dad’s 74th birthday, I re-discovered this piece, my reading of it different now. I imagined how my father and I might have connected over the lesson and imagery. How we might have realized together that the message can be universalized beyond parenthood, beyond mentoring, even, extended all the way to one generation’s role in shaping the world for the next. This is from The Prophet by Lebanese-American Kahlil Gibran, first published almost 100 years ago. Please allow me to dedicateOn Children to the memory of my father.

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life's longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you, yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts.

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow, which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite, and He bends you with His might that His arrows may go swift and far.

Let your bending in the archer's hand be for gladness;

For even as he loves the arrow that flies, so He loves also the bow that is stable.

I think that for all his fervor and unrest, and despite his taste in neckties, as a teacher and as a leader my father was like that stable bow. It is my honor to be here today to witness so many of the arrows he helped direct, and to be one of several that flew all the way here from Poland, Vietnam, South Africa, and other faraway places.

Remarks delivered by the author on 2019 04 04 at UCONN’s Thomas J. Dodd Research Center in Storrs, CT, published on this site with minor edits.